View of USNA Worden Field and Rodgers Road from Hill Bridge.

Senator John S. McCain, III — American patriot, leader and hero — reported to his final assignment today at the United States Naval Academy. He will be laid to eternal rest at the academy’s cemetery on Ramsay Drive. It’s a beautiful place, surrounded by the Severn River, College Creek, and views of the parade field and the Academy’s distinctive architecture. The Naval Academy is a one-of-a-kind place, and graduates, who are known as midshipman during their academic years, are unique.

My family had the good fortune of spending four years at the Naval Academy when my father served as commanding officer of the Dental Clinic. We met our first midshipman before we arrived. In fact, he was standing in front of 50 Rodgers Road when our moving van pulled up — he literally came with the quarters! My parents gained another son that day, and my brothers and I gained just one of many new big brothers and sisters who continue to be part of the family today. As sponsors, we welcomed young men and women from around the country into our home and hearts. One was a swimmer. One played football. One went nuclear power. One went Marine Corps. Several became aviators. Each had that special “Mid” brand of humor and twinkle in the eye that characterized the intelligence and grit they possessed to succeed at the Naval Academy and beyond.

Although I didn’t know Senator McCain, I’ve always admired him and appreciated the ever-present midshipman in him. It’s a kind of curious good humor that respects authority but may require testing the bounds — because you just never know until you try, right? My older brother and I once enjoyed a spontaneous tour of the steam tunnels running under Bancroft Hall. (Pretty sure that was not “allowed.”) My younger brother, at age 4, was the world’s youngest Plebe and enjoyed a camaraderie with these future officers that defied age. At any time of the day, one or a half dozen of our Mids might arrive for a touch of home, including mountains of chocolate chip cookies and homemade popcorn. We loved it as much as they did.

Senator McCain touched my heart for another reason linked to the Naval Academy. Our quarters were on Rodgers Road, with the parade field as our front yard and College Creek to the back. Two of our neighbors, as well as the Superintendent at the time, were former Vietnam prisoners of war. Yet they were our neighbors, our parents’ friends, and their kids were our playmates. In such a unique place, extraordinary people lived regular lives that were, in fact, indescribably exceptional.

Our kitchen window faced College Creek. Nearly every day of the year, my mother had a view of midshipmen running for PT and others rowing crew, since the boat house for the crew team was directly across the creek. From time to time, she would remark “funeral today,” as a procession made its way over the bridge to the cemetery on the other side. This morning, I talked to her as we both watched MSNBC’s coverage of McCain’s funeral procession heading to the U.S. Naval Academy Chapel. Reminiscing about her kitchen window she said, “Those days, I always ended up with a migraine.”

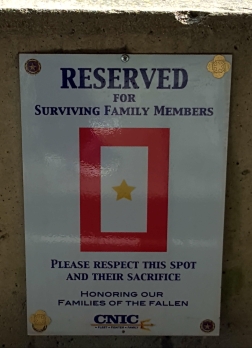

To me, that comment gives great insight into what it is to be a military family. We ARE family, both within our particular service branch and across them all. We are family. The love is real. Each funeral procession is personal.

Last year, I did meet Senator McCain by chance. It was an experience I’ll never forget and always cherish. He was so very kind and real, with that bright midshipman’s twinkle in his eye. Surviving hardship as he did is one thing, but thriving to create such an impactful life of service is a level few attain. Once a Mid, always a Mid.

May the lessons of John McCain’s life help guide America, and may he rest in peace under clear skies on the Severn.

#GoNavy

Several weeks ago, I crossed paths with Senator John McCain at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC). I was star-struck, and missed an opportunity to share an important message on behalf of Americans like me who rely on medical researchers and specialists in order to live a life worth living.

Several weeks ago, I crossed paths with Senator John McCain at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC). I was star-struck, and missed an opportunity to share an important message on behalf of Americans like me who rely on medical researchers and specialists in order to live a life worth living.